Ben Greenberg

Photo by Ebru Yildiz

Ben Greenberg has been obsessed with making and recording music for most of his life. Despite still being in his 30s, Ben counts an astonishing number of credits to his name as a musician, producer, engineer, and mixer, and the diversity of those credits is as staggering as the number itself. Ben began his career working in professional recording studios and touring at the age of 15, which certainly played a role in how prolific he’s been, but his range as a creative is something truly remarkable and difficult to define.

As a musician, Ben is a classically trained guitarist who studied composition at the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music. Ben creates experimental solo guitar work under the name Hubble, but is best known for his involvement with the defiantly uncompromising industrial-hardcore band Uniform and for his time playing with beloved Brooklyn rock ‘n’ roll favorites The Men. He’s also performed with heroes of outsider music like the late Glenn Branca and composer Terry Riley.

Ben’s time on the other side of the studio glass has seen him work with a litany of artists that are seemingly unified only by a desire to push the boundaries of their work in some way. Some of his most notable recent studio credits include working on the lion’s share of releases from tastemaking Brooklyn label Sacred Bones, working with people like Marc Ribot, Depeche Mode, and the legendary Danny Elfman. Since opening Circular Ruin Studio in Brooklyn with partners Randall Dunn and Arjun Miranda, Ben’s been taking on an increasing amount of work honing and mixing film scores, including providing the final mix for Benny Safdie’s critically acclaimed The Smashing Machine.

While it’s nearly impossible to easily define Ben’s fingerprint as a creative, much of the work he’s done embraces a palette of ugly, subversive sounds to remind people that there’s a dynamic range that exists beyond their comfort zone. It’s something that’s caught the attention of increasingly higher profile collaborators, but there’s much more to Ben’s world than noise for noise’s sake.

David Von Bader recently spoke with Ben to discuss his approach to collaboration, the virtues of keeping it simple, the silver lining of the insidious AI music revolution, and the economics of making a living as a creative in the internet age without selling your soul.

David: You seem to be getting a lot more film work these days.

Ben: The work that I've done in film and gaming has expanded a lot since we opened Circular Ruin five years ago. I was mixing scores for Brian McOmber [musician/composer Dirty Projectors, Björk, David Byrne, Kingdom of Silence, Blow the Man Down] before that and now I'm mixing scores for much bigger films and I'm getting the final mix on a number of them–which is something I'm interested in pursuing more of. We recorded for a major video game for the first time this past year and I played a lot of guitar on that, but I can't talk too much about it because we're under an NDA, but it’s really exciting.

David: Is this your very own Steve Vai/Halo moment?

Ben: That was kind of what they were looking for! It’s a sequel to a big game and the first time we got to do anything like that and learning the process for making gaming music was really eye-opening. Game scores are actually generative now, so when I saw Eno, I was thinking about how gaming could be a totally viable platform for the film to live in permanently because these open world games are already generative and that's how the music in them works. You deliver individual stems, but nobody mixes them and the generative engine puts it all together. Those engines are proprietary to each open world game, but I think they do a similar thing that Brain One is doing, just with the music stems instead of footage. Those engines work in the same way as Brain One, where it's a human-coded generative program, not AI. It's a fascinating approach and very different from what I’m used to doing, and that alone made it worth getting involved in that project. What I found really insane is that it's been done that way for something like 10 years. The gaming industry is lightyears ahead of everyone in that respect.

David: Being responsible for the final mix on a high profile film like a Safdie Bros movie like The Smashing Machine and submitting a collection of unmixed cues to be reworked through generative software for a video game is wild contrast. Can you compare those experiences and how you approach them?

Ben: What's so interesting about any generative process is that there is no final say. When you're dealing with a film or mixing a record, there's a committee that's making decisions and you're the point person that actually puts your hands on the stuff to realize those decisions. With a film, there can be 30 people involved in that process and it can take a really long time to get anything done. Small decisions can be debated for weeks and that process often forces extensions which require a tremendous commitment of resources and can quickly triple a budget just to get a project done. So it's not just how you approach the decision making from a creative place, but the pressure to get it done as efficiently as possible. It’s a huge contrast to participating in a generative process, where there's still pressure to deliver high quality work, but without the idea of finality. They’re so dramatically different.

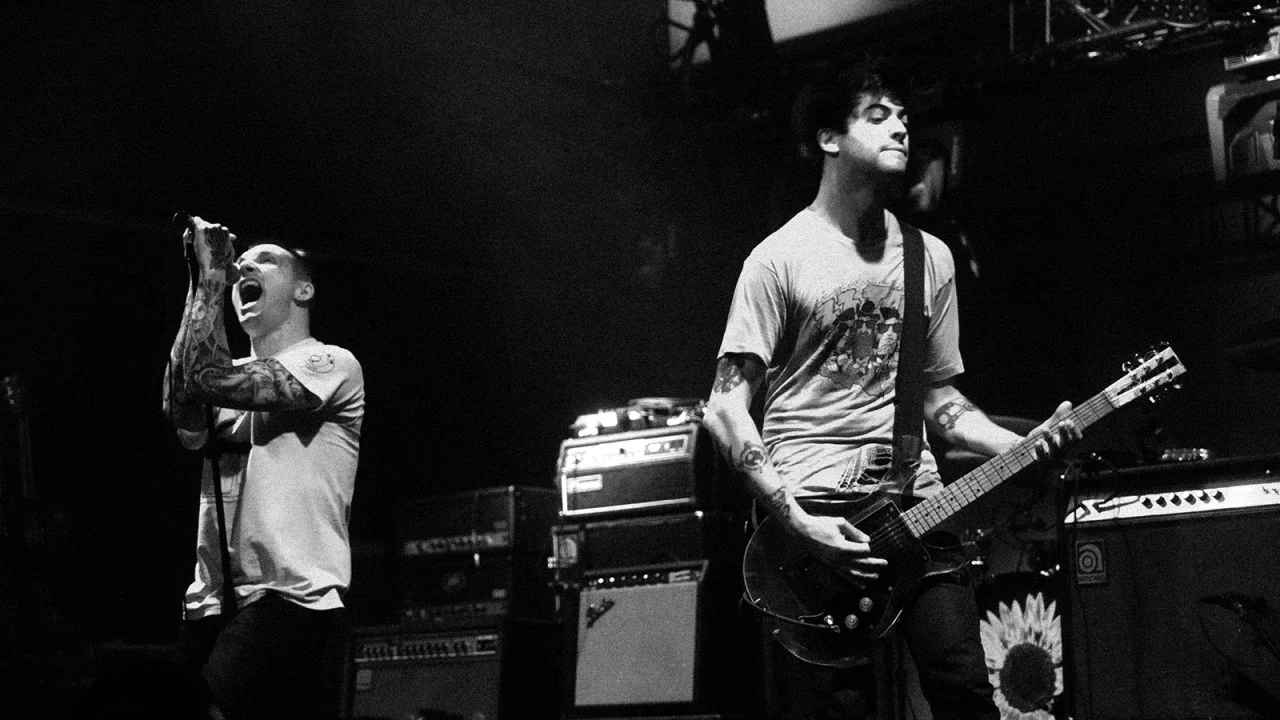

Ben performs with Uniform at Market Hotel in Brooklyn.

David: The idea of finality has kept a lot of great creatives from putting work out. I think Keith Richards once said, or paraphrased someone else that said “It doesn't really matter if you have a good idea in the studio, it's whether or not you can make decisions.”

Ben: Absolutely. It’s about having the confidence in your ideas or guidance. There is no objective right or wrong, it’s about how it feels to each individual–so what feels right to me is all I’ve got. The work becomes more about whether or not people trust that and if I can make the conversation move in a constructive way.

Making creative decisions under pressure can make for difficult moments, and especially so with young musicians or with film producers that are less experienced. They tend to get really focused on the decision making and I’ve found it’s important to be simple with it, and the important part is ultimately to move past the decision to get to the results and to experience that. People get option paralysis when they’re inexperienced. For me, with the amount of records I have under my belt, I find I do have to stop myself and be more patient in those moments.

David: Are there any magic bullets to getting that job done in the studio?

Ben: Something that I do a lot in the studio is try to be less specific. Not suggesting “Hey, we need this brand and model distortion pedal” but asking “What’s a cool distortion pedal?” Knowing we need compression on a track and keeping the conversation to “Tube or solid state?” and focusing on the fundamentals, because that's ultimately what matters. There's going to be different details and nuances and colors, but I’ve found when you really get into it, people just aren't that granular. The records that people reference typically weren’t made by people being granular when it comes to specific gear choices. So I’ve found asking simple questions is how you get there because people get distracted by the bright lights and marketing of gear.

David: It's so hard for most creatives to separate themselves from the emotional side of the work when decisions need to be made. I can’t imagine dealing with a committee of 30 people and things staying constructive and democratic. What’s your approach to collaboration and what’s worked for you in those scenarios?

Ben: I've seen it go a lot of different ways and there is no one approach that works for everybody. You have to be empathetic, but you also have to be committed to your own vision. It’s about balancing those roles. While having more people in the conversation can slow things down, I’ve also had moments where it’s made it simpler because a room full of people are often looking for leadership, especially when it comes to the hard decisions. You have to believe in your opinion and you have to present it in a concise way that's sensitive to the needs of who you’re working with.

A big difference I've found between making records and working on films is that when you're working on records, it's usually an equal playing field; everyone might not have an equal say in the ultimate result, but everyone has equal access to participation usually. In film, there's a hierarchy and even if you have a higher role on paper–like doing the final mix–it's a technical role. You’re working with people whose job it is to be creative, but your job is to come up with creative solutions or interpretations to translate and achieve those ideas. On a record, it's totally different. When I make a record, it’s like “Hey, I doubled the bridge when I was mixing your song because it sounded better and I also added a kick drum” and people are like “Wow, thanks! You totally changed my song and you were just supposed to be mixing it.”

“You have to be empathetic, but you also have to be committed to your own vision. It’s about balancing those roles.”

David: Mixing a record or score is a vague concept to a lot of people and I think under-appreciated because it’s often just seen as louder/softer, or a fade here and there, rather than the sound shaping and arrangement that’s really done.

Ben: Yes, and the skillset translates very directly. You're still thinking in additive versus subtractive ways and you're thinking about the whole frequency spectrum, things like frequency sharing versus isolation and how sounds gel together versus how you give them relative clarity. You're thinking about the total aural experience.

David: It may be an even darker art than mastering, which most people can’t explain.

Ben: We actually started officially offering mastering at my studio for the first time this year. We've been doing it for friends under-the-table because it really is this dark art that nobody understands, but we started offering it above board because it’s ultimately just ears and gear. I have nothing but respect for the folks that specialize in mastering, but we looked at the people that were doing our favorite work and found they’ve become incredibly expensive. That's changed over the years, and I haven't seen the record budgets or fees that producers and engineers and studios charge rise, but the mastering bills have doubled and tripled. We thought we could provide a more accessible experience that provides the same level of quality.

Ben and Uniform bandmate Michael Berdan-Larsen. Photo by Ebru Yildiz.

David: That egalitarian approach is an interesting facet about your career. You’ve worked on huge projects like Safdie Bros films and with luminaries like Danny Elfman, but you also still take on unsigned baby bands. Is that just a byproduct of coming from the punk world, and how do you balance your time management with such varied projects and budgets while still making a living and progressing?

Ben: Part of it really is just making a living and needing to patch together X number of gigs a year to make that living. It’s a faux pas of the engineering and production world to avoid talking about the brass tacks of how you earn a living and to just lean into talking about the creative and the technical side because it's fun and sexy.

I don't say “yes” to everything, but there's a survival aspect that I'm always conscious of because it's really hard to make a living out there in any creative field–but especially in music. It’s so devalued culturally now, so I always have my eyes open regardless of profile because while it could be interesting and fulfilling creatively, but also because it has to all add up. If I only said “yes” to the things that were the biggest look, I would work half as much as I do.

David: Are there any blanket statements you can comfortably make as a creative with so many credits to your name?

Ben: Hard work and dedication are what make great art and that's what has always made great art. People get distracted by consumerism or by imagery or by the social participation aspect, which I think is important on a spiritual level, but that's not how most people are interacting with it through social media. They're interacting with it on a covetous level.

David: For example, you're not going to AI your way into playing guitar really well.

Ben: Yeah, or making truly beautiful music in general. When AI music first reared its head in 2017, everyone I spoke to was freaking out about it like “This is really bad.” I was like “Eh, it's not great, but it's going to force the conversation” which is good because we've lived in a world that's been trying to sell entertainment as art for decades.

When I was 13, that was the thing that I was angry about. I was yelling at kids in school like “You like entertainment, you don't like music!” I think the cool thing about AI is that it forces that conversation for people who'd never thought about it before, which is the most of the mass music listening audience. I think it's really cool that everyone has to think about the value system behind what they're listening to now–even if that's not specifically how they're thinking about it, they have to consider it on some level because now there's human music and there's not human music. AI's take on human music can be a dead ringer for it, but it’s never going to capture the real thing–just the entertainment of it. There’s a big difference.

Part of the reason I think everyone's going back to the music of the ‘90s is because that was a time when even the biggest labels had to try and sell authenticity. People very suddenly wanted something that felt “authentic” for the first time in a really long time, and it’s hilarious because that's a simulacrum of authenticity. But it's interesting because we're currently in the least authentic era in terms of most music and media, where most things are a copy-of-a-copy-of-a-copy at this point, and people are still reaching back for the thing that felt authentic, even if it was just something that was sold as authentic rather than being actually authentic.

“I think it's really cool that everyone has to think about the value system behind what they're listening to now–even if that's not specifically how they're thinking about it, they have to consider it on some level because now there's human music and there's not human music.”

Ben performs with his experimental solo guitar project Hubble.

David: What are the things that you're excited about now in sound and music production, and is there anything you think is being really overdone?

Ben: There's been a big focus on going back to the analog feeling in production and mixing for the last 10 years. All of these studios are buying and maintaining tape machines again for the first time since the ‘80s, and using vintage tube compressors and tube microphones, and this Nashville sound where everything is warm and gushy and thick. That's good and bad. I love the way old records sound and I love those recording techniques. I came up working on tape, and I love the way slow compression sounds and that kind of saturation and coloration, but I also think it's been done-to-death at this point. Every vocal on the radio is so distorted and manipulated, and so aggressive–even on the prettiest songs.

David: Have we reached the saturation point of saturation?

Ben: That's how it feels! And it's what people expect across all genres now. Everyone is asking “How can we distort it and make it sound fucked up?” I love doing that obviously, but I think it’s being used to cover for a lot of people not getting great sounds as a starting point.

David: There's a difference between a creative distortion that accentuates a recording and an effect for effect’s sake. That said, I think it's pretty rich that the guy from Uniform wants everyone to dial back the distortion.

Ben: That’s funny! Randall [Dunn, Greenberg’s partner in Circular Ruin] and I joke a lot that our job is distortion curation. People come to us to curate their noise and distinguish between good noise and bad noise, and mixing these days is largely that because people expect all these different types of saturation. But I’ll get clean stems and processed stems from people to mix and the processed stems will all have the same distortion because they're obsessed with that sound and their demo is already irresponsibly loud, but they want me to try and beat it somehow. Don’t get me wrong, I still love making fucked up sounds, but I also wonder if there isn't a way for things to be more interesting, where we can still utilize these sounds and textures in a broader picture where there's depth and nuance, and a foreground and a background. You can’t really do that with exclusively distorted sounds and I think that's much more important.

Ben performs with Uniform.

David: As a studio owner that’s heavily invested in the gear and space to work the traditional way, but also as someone that does a lot of work mixing people’s home recordings, is there a creative X-factor (besides the high-end gear) that you think the home recording generation is missing out on by not working in a traditional studio?

Ben: The benefit of others' experience and learning hands-on and directly by observing how people make decisions based on their experience. That is the number one thing that's missing. There aren't that many places for a kid to get an internship and really learn how to do it, and there also aren't many older, experienced folks that want to pass it down anymore. Just getting to be a fly-on-the-wall was the whole point of coming up in the studio system. You’d get coffee for people, set up microphones, wrap cables, and you would learn things when you weren’t doing that and sitting in the room waiting. That's how I learned how to cut tape, that's how I learned how a recording desk works, that's how I learned about gain structure. That's how I learned about how to talk to musicians. There's no replacement for just being in the room and it sucks because there's no solution for it right now.

At the same time, there are examples of folks who are coming up on their own and learning through whatever means they can and working out of home studios and making records that really land. That's really impressive.

David: You've got a super diverse discography and your credits really are all over the place. If you had to define what attracts artists to working with you, beyond the credits you stand on, what would it be?

Ben: I do think it is largely the credits I stand on, but that's the case for anybody. What I can speak to is when things go well and why I think they go well, and I think that relates best to what you asked. When things go well, I think it’s because we're communicating really freely and fluidly and with respect for each other. We're listening to each others’ ideas and it's a two-way street; we're having an open dialogue and everybody's headed towards the same goal–even if they don't all see the same path. The records and the projects that go well, that's what's happening. Those are the situations that I'm always looking for and I hope that's what people come to me for. When it's not a fit, it's because some aspect of that is missing–the trust or the communication or the ability to have a shared vision.

David: Do you have any advice for vetting clients before you get too far down the road on a project and find it’s not a good fit?

Ben: That has become one of the hardest parts of the job. It’s really hard to tell what someone’s going to be like when they’re feeling really insecure and being criticized and how they respond in those situations. It’s very hard to get a sense of from someone who's not just a stranger to me, but an artist who has a persona that is often constructed to a degree. You have to find a quick way to get to the truth of who someone is, or at least the truth of what they want from you.

It used to be easier to tell what somebody was after and if it was going to be a fit. I think there's a scarcity mindset in the music world now that's much more intense than it was even five years ago. I think COVID had a big impact on that and obviously the industry has been shrinking for 25 years. At the same time, you have kids that are growing up seeing it all on their phones and they want to just be on the other side of that, to be seen the way that they see things. Everything else in their lives is point/click/acquire, so there's an expectation that it's going to be the same way when you're creating something. Obviously that's not how it works when you're working on something creative, it takes time, experience, hard work, and dedication, and those aren't really the values that are being championed in society in general.

My best advice is to keep it out of the written word. I try to talk to people as much as possible and I try to keep it off email and off text because I'm very literal and succinct when I write, and that isn't always what's called for. I also try to be as straight up as possible with how I want to do things and what I want while asking a lot of questions to get a sense of where they're coming from.

David: I think a lot of people are under the assumption that you hire the guy and it magically gets done, where I’ve found the role of a great producer is more of a sherpa that guides an artist up the mountain.

Ben: And they may not necessarily know what mountain to climb. As long as I do, then that is the whole point of hiring me. If we can't have an open dialogue, whether you're concerned about the direction a project is taking or feeling good about it, or just want to turn the snare up, it makes things really difficult. I've had increasing experiences with younger artists where they just don't know how to put what they want into words. It becomes a huge barrier when someone's having trouble articulating themselves, or hearing what it is, or thinking critically about it, but I think it gets to this larger issue of communication and how people relate to each other in general these days. It’s all connected.

“The sounds and feelings that I'm interested in have never changed; they’re intimate and carry depth, and it's that balance that I love. How close something is to you, how far away it feels, or how a collection of sounds can feel physical around you. There's a certain immersive quality that I've always looked for when I'm working on music with people. I want it to feel overwhelming so that the emotional content is undeniable.”

David: You recently worked on a relatively sparse and traditional singer/songwriter record with Mark Ribot, who is no stranger to fucked up sounds, but you’ve also worked a lot with people from the noise world and the fringes of the alternative metal world, and now films and videogames. Is there something in your approach that applies across the board to such varied projects?

Ben: The sounds and feelings that I'm interested in have never changed; they’re intimate and carry depth, and it's that balance that I love. How close something is to you, how far away it feels, or how a collection of sounds can feel physical around you. There's a certain immersive quality that I've always looked for when I'm working on music with people. I want it to feel overwhelming so that the emotional content is undeniable. Whatever it is is going to stare you right in the face and there's nothing you can do about it. That's always been where I've headed, and that's not how everybody thinks about music and sound. That can be a big litmus when I'm deciding if a project is a good fit or not. I think that those qualities come through in almost everything I've ever done, whether it's a Nels Cline Trio or a noise record. I want it to feel like you're in the room and surrounded by it and can't get away from it or close your eyes to it.

I also think if someone's coming to me, they're looking for something else. They're not looking for a sound that's been repeated over many records, they're looking for someone to challenge them and push them to do something different, I hope. To provide a contrast to whatever they've been doing or push them deeper into the contrasts within what they're doing.

I'm obsessed with hearing things that I haven't heard before and that's how I think you get there. I've never been very interested in recreating someone else's idea of a thing. Can you make it sound more like this example of a genre that's very well-known and widely understood? No, you should turn the record over and call that guy for that.