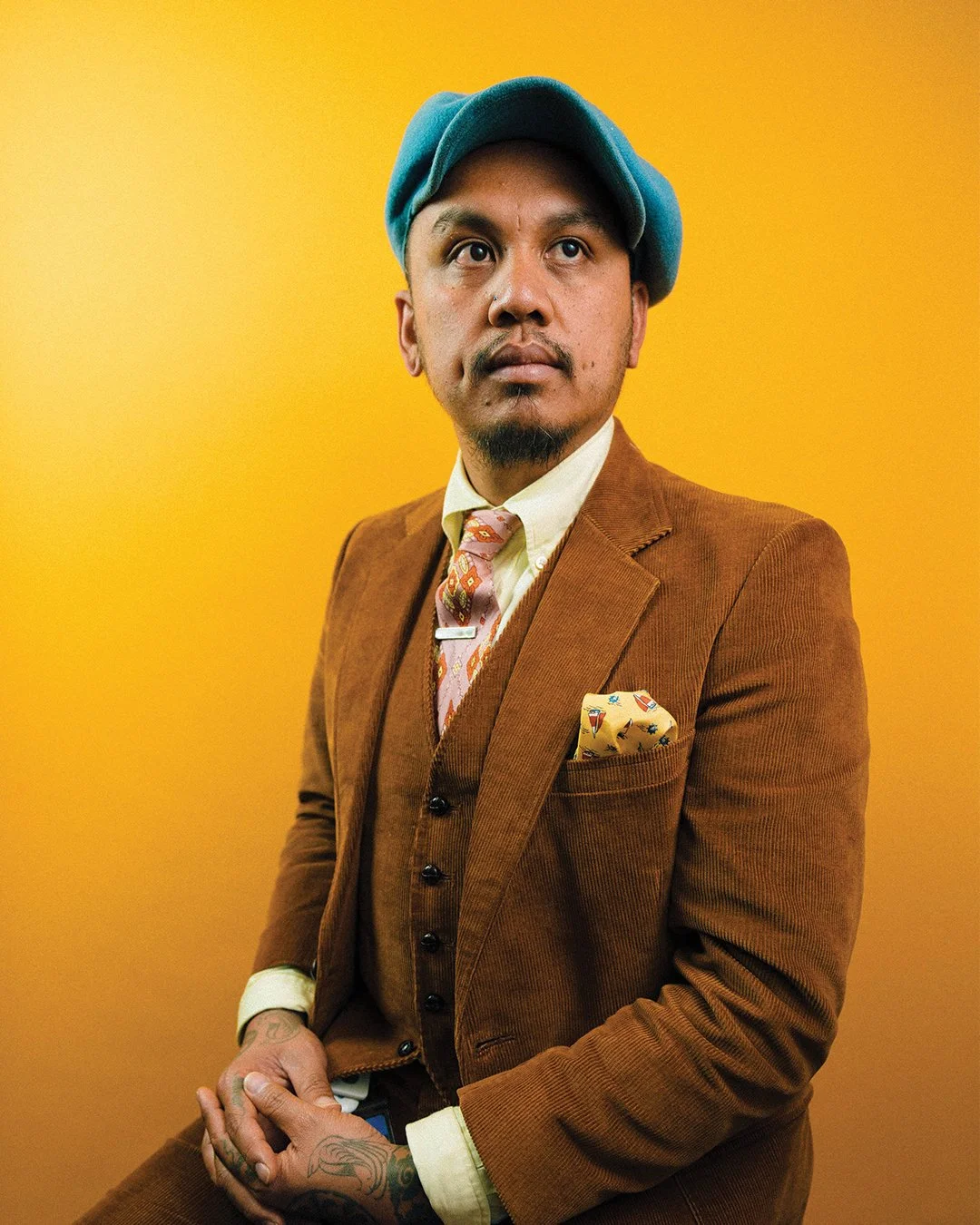

Everett Katigbak

Multi-hyphenate artist and designer Everett Katigbak has worn all the hats. In 2007, Everett left his “dream job” as an exhibition designer at the Getty Museum to join Facebook in its Wild West days, where he and colleague Ben Barry quickly started a skunkworks art studio and print shop inside the budding social media giant. Dubbed the Analog Research Laboratory, the initiative helped define company culture with a human-first, rule-bending approach to creating art in a corporate environment. In his later work at Pinterest and Stripe, he found spaces to bring physical media into the fold in a meaningful way for digital companies.

While much of Everett’s output has been focused on storytelling and brand identity, it’s been his uncanny ability to inspire creativity from within and help tech companies stay in touch with their humanity that’s set him apart more than any specific visual work. Everett’s track record of getting major companies to ask “Why not?” and roll the dice on ideas that may not make sense on paper, but do wonders to shape the bigger picture is well-established.

Now he’s asking “Why not?” of himself.

Everett recently left his role as the first designer and Creative Director of AI company Anthropic to row his own ship as an independent and explore the other AI: Analog Intelligence.

Gary Hustwit and Everett looked back at the artist’s maverick approach to creating in a corporate space and discussed the value of embracing your humanity, even as a digital creator.

Gary: I’m interested in this interplay between digital and analog creativity. Making tangible things as a counterpoint to digital seems to be a theme for you in the places you’ve worked.

Everett: I'm a big proponent of whatever the fastest way is for you to articulate your ideas, and for me and the type of work I do, that's making it by hand. I'll make a prototype out of foam core or something. I learned that working at the Getty Museum; we'd make scale models of everything, then we'd make full-sized models, then we’d send it off to be fabricated. We were able to see that one idea behind the design the whole time. Also aesthetically, all the mistakes and the nuances in something are 100% your own if you make it by hand. I think you lose something with all the digital precision.

There's also a cognitive offload that's happening with AI specifically for creatives. One of my mentors, the legendary art director Lou Danziger, said the most powerful tool we have as designers is "Microsoft Word," meaning that you have to be able to articulate your ideas clearly. But when we start using AI to write for us, that muscle starts to atrophy. When we rely on prompting to get the final result, we become that same nagging client or stakeholder that drains all of our own creative energy.

Gary: Yeah, usually people think everything they do should be perfect and look “professional,” whatever that means. If you’re doing something by hand—especially if you're not like a trained artist—it’s going to be flawed, and most people aren’t comfortable showing their flaws.

Everett: I'm not saying that everyone needs to make everything by hand. In this world of AI—where everyone's talking about tools that can amplify your creativity or accelerate your output—I think those tools can also amplify your insecurities as a creative person. If you don't feel confident in yourself and your ability to articulate your ideas making them by hand, then the outputs from these digital tools is just going to exacerbate some of those insecurities. I'm not advocating for people not to learn technology; I'm still a huge fan and optimist about technology, but I think most young designers jump right to the computer. If all that technology went away, you would just have yourself, and you still need to be creative.

I think you just have to be really in touch with your humanity—especially as a creative person and as someone who makes logos and brands and tangible things. I think a lot of people bypass art school and jump right into design, because you could very easily get a job and make tons of money without art school. But what they're missing is that idea of focused attention. In art school you start with a brush and some gauche and just making colors. It's very rudimentary, but a lot of folks miss that these days.

Gary: What were the early days of Facebook like, and how did the Analog Lab get started?

Everett: Facebook was my first gig in tech. It was 2007, so still very early days there. When I started, I asked them “What should I be working on? What do you want me to do?” and they were like, “I don't know, go figure something out. Go talk to those people over there and see what they're doing.” It was a real Wild West situation. Very nebulous, but also so much opportunity, and I had never experienced that before.

The Analog Lab started because my co-worker, Ben Barry, and I were basically print designers that were suddenly in this sea of engineers and tech people at Facebook. It was really just a side hustle that gave us a space to keep getting our hands dirty. Facebook was doing a lot of conferences for the engineers at the same time and they asked us to design stuff for those. We didn’t want to just design posters on the computer and send them out to a printer, so Ben and I decided to make all the stuff by hand. We started screen printing things at night and designed all the tables for the conferences and it was just the two of us. It created this very different aesthetic.

Back then, Facebook was a petri dish of weird people and ideas and cultures, and they really encouraged agency and entrepreneurialism. If you had an idea, say to build a digital product or something, you could just go off, build it, and then come back and be like “Look what I built.” That's how things like the “like” button got made. People designed things and let their prototypes do the talking. For Ben and I, these very physical designers, we just adopted that philosophy for our own projects and people started to resonate with it. We were using a guerilla street art approach to start stirring the pot and to try and get people to think very differently about their jobs. We were building technology for scale, but we were also building it for humans, and that was getting lost in the hype of silicon valley those days.

Some people questioned why we were doing it, like “Why are you guys tagging up our office and putting all these very provocative signs on the wall without permission?” But the more we did it, the more Zuck [Mark Zuckerberg] and the execs were like “Keep going, don't listen to people.”

Eventually we started hosting workshops for the different teams, like screen printing workshops. Bring your team to our space and we'll help you make things. Hackathons were a big thing for us and we’d bring our equipment out into the middle of the office while people were up all night coding and we would print things right next to them, or I'd pick a wall and do a live mural painting in front of them while they coded.

Ben and Everett at the original Analog Lab at Facebook. Photo by Jesse Chehak.

Gary: Was the Analog Lab something you became known for outside of Facebook? Like when Stripe brought you on, was it because they thought “This guy can make our staff more creative?”

Everett: I would never say it was my full-time job description, but it definitely was something I became known for. If anything, it was more about being like a rebel inside of a company or just having agency and being able to help shape an internal culture. Using that to inspire folks to build things externally, and to align people around a vision. After Facebook, I went to Pinterest, and I was there for a good three years as well. It was a similar experience when I started there because it was just 30 people—really small. It made more sense in some ways because Pinterest was a very craft-y brand. When I went there and bought a letter press and started making stuff, it became part of their vibe because they were all about inspiration and craft.

“If anything, it was more about being like a rebel inside of a company or just having agency and being able to help shape an internal culture.”

The thing that I guess is the thread through all of my work was asking “What is the human approach to help build this brand? What is their vibe?” The Analog Lab had a very punk-rock, guerrilla aesthetic, and that's because Ben and I were these young designers. By the time I was at Stripe, it was a very different world.

Stripe was a financial payments company and I was thinking about what the human story was that I wanted to tell. I started pitching them a lot of films to help tell those stories and we built Stripe Press, which was about releasing physical books. I think that was the grownup version of the Analog Lab. Seeing it on paper, people would ask “Why would you build a publishing arm for a financial company?” But it became like a huge part of their brand.

Gary: Do you think the audience for the books and films was primarily external, or was it internal as well?

Everett: Both, but I would say internal because John and Patrick, Stripe’s founders, were huge bookworms. They believed that there were all these like great ideas that didn't have a home at a traditional publisher, and that we should just do that and we could make them cool. We could focus on the craft of publishing, but do it in a way that wasn't like a typical publisher. We had no formal publishing experience and were just figuring it out, but I think it ended up having more impact and staying power than anything I've worked on it.

Everett presenting cover art for the first book on Stripe Press, "High Growth Handbook"

Whenever people question what I’m doing, that's when I know I'm striking a chord. Everyone was like, “Why are we doing this? What's the point? What's the ROI of this?” We were a tech company with all these scaled revenue streams from enterprises and they're like “We're losing money on these books. It's not a revenue stream, it's a weird business model.” Really it's not about any of that stuff, it's about the ideas, it's about the craft, and it's about the kind of brand investment we're making.

Gary: How did that manifest at Anthropic?

Everett: I'd say that was one of the craziest rodeos I've been a part of in the sense that the AI world just exploded. It's unlike any other facet of technology. It felt like we need to do this and we're just going to run in that direction, but we don't know what we're actually doing. You're hiring people, you're competing with Meta and Google, so it's like this crazy Game of Thrones situation. For me, it was like ‘Oh, this is amazing. I'm working with these AI researchers and I'm helping them tell better stories about science.’ They would have a project that they want to publish a paper on and I could help them articulate it in a way that was bigger than just the research community—that could expand to broader audiences. That's where the seeds of the brand identity took place: Trying to help the researchers. Then we launched Claude and it became like more of a consumer brand and it was off-to-the-races.

We started doing things as fast as we could, but for me, the root of the brand was a human-centric thing. It's in the company name itself and I think that was intentional, but they didn't know how that would manifest as a visual identity—Anthropic being about humans and our time on earth and those ideas. I realized it wasn’t an AI company, but a human-centric company that just happens to be building AI because that's the most impactful thing for our society right now.

Gary: You left Anthropic after two years. Was it just the radical growth, or did you feel like you had things you wanted to explore that you couldn't do in that kind of environment?

Everett: I'm no stranger to rapid growth; I started at Facebook when there was a couple hundred people and left when there was 8,000. and that was over a five-year period. Every company I’ve been at has had a hockey stick growth like that. So I'm conditioned to these hyper-growth companies. I don't think you age out of tech, but the older I get, the less I excited I am about the grind. Going independent was something that I’d put off for the longest time and I think part of it was the timing of technology in the world, and this idea that you can build anything because you have all these tools at your disposal now. Working inside a company took on a different meaning for designers and for me, I was like ‘I think I could stand up my own thing and be successful at it.’ I had all these ideas brewing and I was like ‘I’ve just got to do it, otherwise I'm going to work here for the rest of my life.’ Sometimes I blow things up in my life, especially when I'm feeling too in a groove. I’ve got to shake it up.

Gary: I think it's interesting that you’ve chosen to document this transition and the feelings you're going through, and putting that out there with your Instagram posts. Why did you feel sharing that was important? Was it mostly to verbalize what you’re feeling, or to connect with other people going through the same thing?

Everett: My buddy Soleio and I worked at Facebook early on, and he later became a big investor. I told him I was thinking of going independent and asked if he had some advice on how I should frame the stuff that I do. In many ways I'm this jack of all trades, and I join early stage companies and I help them figure it out. I'm not just a video producer, I'm not just a visual identity person, you know? He said, “I think you should turn the camera on yourself.”

That had never really crossed my mind. Even though I was working at the dawn of social media and at Facebook at the earliest stage, I rarely posted anything. I think I wanted to explore that because I thought it was a good mix of all these things I like to do. I have all the tools that basically let me make films right now from my bedroom, and I can distribute them on social media—but in a very different container. And now I have all this experience so I was like ‘How do I put this out there to help people?’

There's really no playbook for it. You just start making stuff that sucks until it gets better. That's where I'm at right now; I’m fighting through the cringey moment where I'm like ‘Ah, dude, this is corny.’ But I also don't care, if people don’t like it, they can swipe past it and it's no big deal.

Gary: I think the things you're talking about are important for creatives, and they’re important for all people at some level. The post you did about being a failed musician was interesting. I forwarded it to a friend who I was just having that conversation with, because I never consider myself a “designer.” I design lots of stuff, but I would never say, “Oh yes, I'm a designer.” Could you explain how you framed it in that post?

Everett: When I first joined Facebook, your business card had this little area where you could put any text you wanted. It was this weird thing were they were like “Oh, what's your quote?” and I didn't have one. Then I came across that quote from Ornette Coleman, who said, “Music is a verb.” That really stuck with me because I came from a musical background and I wasn’t doing the thing that I was raised to do. My natural state is being a musician; it's all I knew and then I figured I just had to be a designer because I’ve got to make money. I never made it as a musician. I wasn’t doing the thing I’d really aspired to do. Something had allowed me to accept that all creativity is a physical thing, and if you're not making that thing, then you can't call yourself whatever it is.

“There’s really no playbook for it, you just start making stuff that sucks until it gets better.”

Gary: Or if you're not doing it professionally. The idea that if you're not doing it for money, it isn’t valid. Again, I design stuff, but that's not my job. It's just this thing I've learned how to do. I didn’t go to design school, and while I know enough about design to be able to make a poster or a website, I would still never call myself a designer. I just feel like I haven't earned it or something?

Everett: And I think that's the thing we all tell ourselves. It's like some form of imposter syndrome. But if you're designing stuff, as long as you do it with intentionality, then you’re a designer.

Gary: I like what you said in that IG post, about how you wake up every morning now and just play guitar. Not as a means to an end, not because you want to “make it” as a musician, but just to get your creativity going. That's a great idea.

Everett: I think designers and creative folks—especially if you're a professional—you do it for your day job then you have side hustles. For some reason, everyone I know is now a ceramicist! They're like “I work at this tech company and on my off days, I go to the studio and I throw clay into pottery.” All of that stuff, all of your side hustles, feed your creativity. I think people decouple those things too much in their brain, but you need that to create this flywheel. If your day job is all output, you need some kind of creative input, otherwise you're just going to dry up.

Gary: That's good. I also like that post that you did about being an introvert.

Everett: Thanks, I'm glad you got that! I don't know, sometimes I just put this stuff out there. Like I said, I feel it's cringey, but I'm glad that some folks actually get something out of it.

Gary: I’m normally am one of the louder voices in the room and as a director, I'm going to express what I think the project should be, so it's interesting to hear you talk about the other side of that equation.

Everett: I think design, in many ways, is a natural fit for introverted people. In many ways designers are actors; you’re thrown into a project that you know nothing about and you need to try to understand it and help them articulate it. You have to be a sponge and be able to soak in all the nuance in a short amount of time and then express it in some meaningful way. I've always considered myself hyper-introverted, but somehow I've been able to be in the room with people like Zuck, or John and Patrick at Stripe.

There's something about owning your perspective, and your confidence, very quietly. I think that instills confidence in other people that I work with. They know I can deliver and that I’m not the one who's always saying stuff, but is consistently showing it through my work. People like designers feel like they need to go climb that ladder of management and leadership, and then they realize it gets them further away from the creative practice. I think you can still grow in a leadership position and not have to be this an extroverted person.

Mark Zuckerberg, Frank Gehry and Everett Katigbak review environmental design at Facebook.

Gary: Like the work is about the making of things and not necessarily talking about it.

Everett: As a designer, you have this superpower to make the thing real, and that gives you credibility. It's a different skill. I’m not saying introverted people need to come out of their shell to grow their careers. I don't necessarily think you have to learn how to be extroverted, you just need to know how to own your work and let that do the talking for you.

“As a designer, you have this superpower to make the thing real, and then that gives you credibility. It’s a different skill.”

Gary: So what's next? What do you want to do now?

Everett: It's weird because I have all this stuff lined up, but without the structure of being at a company I’m just trying to figure out how to do it for myself—how to set that structure. I've been working as a producer on a feature documentary about Luis Valdez for longer than I was at Anthropic, and that's getting broadcast on PBS next year, so that's a big thing. And I've just been trying to figure out my own creative practice, so I'm talking with some prospective clients.

It’s funny, people say to me, “Where are you going next? I want to invest in that company!” because when I went to Facebook, everyone was like, “Why would you go there? That's a dumb college website!” and then it blew up. And then I joined Pinterest when it was early stage. Then I went to Stripe early stage. People were like, “That sounds boring, it's just a payments company.” And then it became this huge business juggernaut. And then Anthropic and all the growth it’s had.

So, I guess the natural thing for people think is, “Oh, whatever company you work at next, you must have found something.” And for me it's yes, I’ve found something, but it's myself. I think it’s time for people to build their own personal brands and put themselves out there. You can do crazy, cool, big things with all the tools we have now. So that's where I'm exploring. I'm trying very hard not to revert to just working at another company. I'm going to see if I can make my own independent practice work.

- Follow Everett on Instagram.

- Visit Everett’s website.