Ebru Yıldız

Ebru Yıldız, photo by Lieh Sugai

Ebru Yıldız’s portraits pull off a magic trick of duality. The New York City-based photographer’s images telegraph the essence of their subjects in an intensely direct way, but they’re also instantly recognizable as photos Ebru’s made. It’s a rare balance between artist and subject that’s incredibly difficult to manage, and one that speaks to Ebru’s talent and vision, but also her genuine passion for the work.

The artists in Ebru’s massive portfolio range from baby bands still cutting their teeth in gritty clubs to A-list pop stars and some of the most important, paradigm-shifting artists all of time—including David Byrne, Laurie Anderson, and Debby Harry. Ebru crafts unique visual worlds that she tailors for the artists she shoots, but they all feature her signature touches: a striking use of shadows, an air of drama, and an almost confrontational intimacy. Her photos feel remarkably substantial, but never pretentious.

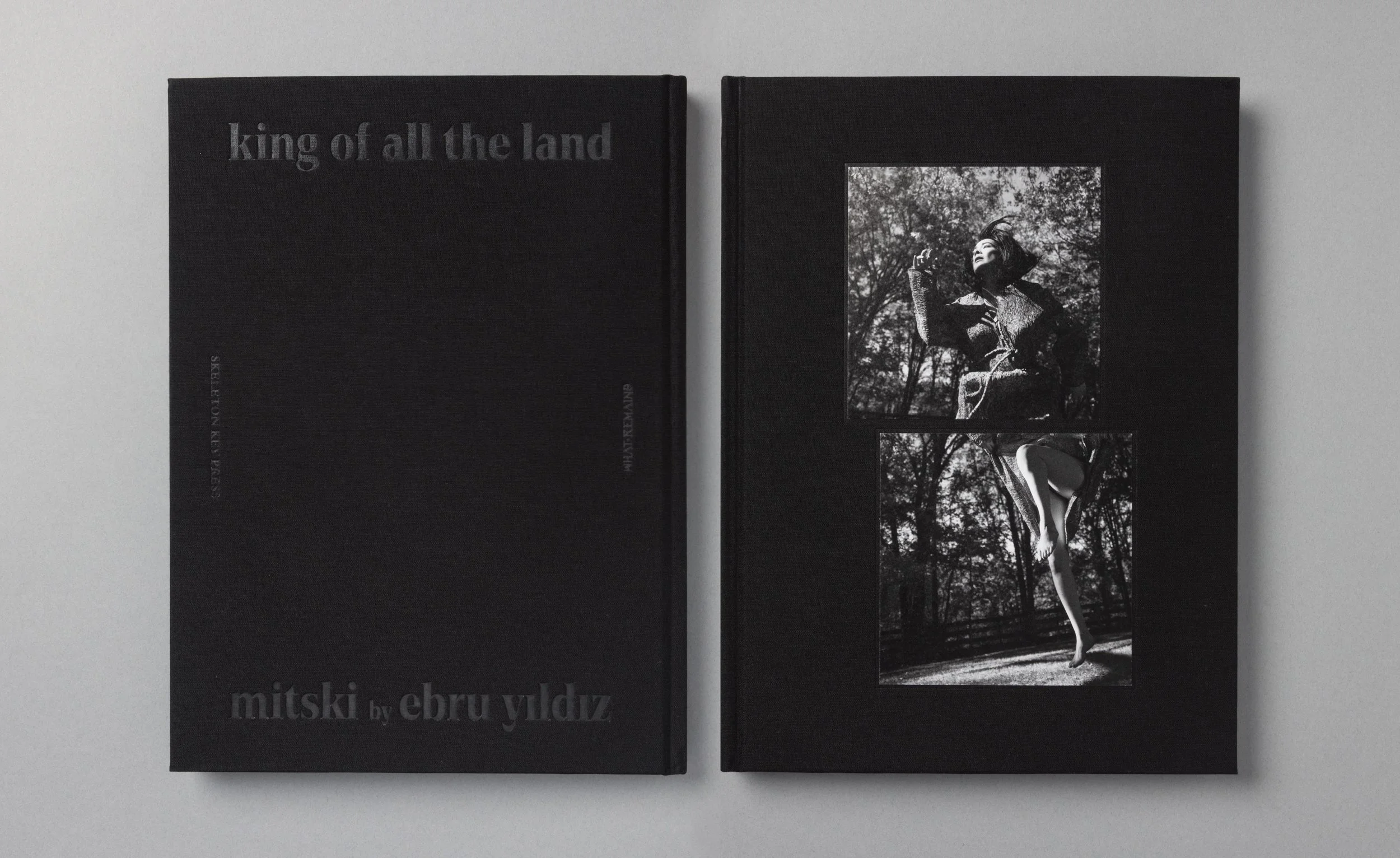

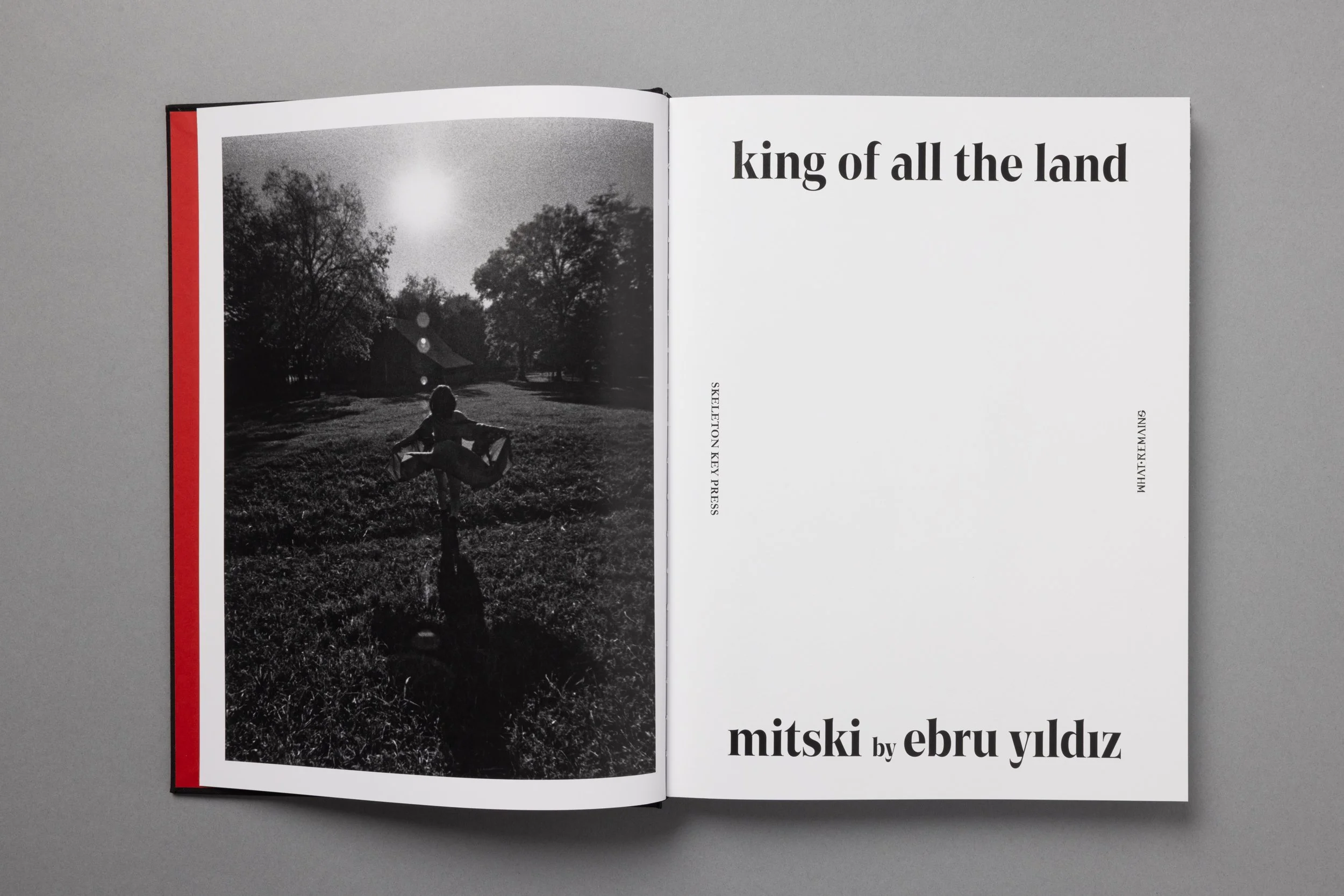

Ebru’s love of photography and a desire to actively fight the impermanence of the digital age recently inspired her to start What Remains, an independent photo book publisher that she founded with partner Mitchell King. The freshly-minted publisher’s first release is a beautifully designed 182-page book of photos Ebru shot of beloved singer-songwriter Mitski titled King of All the Land: Mitski by Ebru Yıldız.

While preparing for the release of King of All the Land…, Ebru spoke with David Von Bader about the value of slowing down, the psychology of portraiture, and why she’ll always come back to photo books.

David: You’ve said in the past that you didn't like how your concert photography was used as news content because it felt impermanent. How do you combat that feeling of impermanence in the digital age?

Ebru: That’s a big part of why my partner Mitchell and I recently started our book publishing company. We named it What Remains because it feels like we’re making what will remain after we’re gone. When I first started, digital cameras weren’t in fashion yet. Digital photography increased the pace of everything, where you'd go to a show and document it, file those photos that night, and by the time you were eating your lunch, everything you’d poured yourself into the night before was old news. That shift had a really weird effect on me and made me want to go backwards, so I went back to film photography to slow myself down. Eventually I started making photo zines because I wanted to make things that could be left behind and that people could go back to and look at.

I have magazines that I've kept for decades because there are shoots in them that I love going back to. With websites, it just feels really impermanent. It’s something I struggle with these days. I was recently thinking about a project I did for Pitchfork about the music scene in Istanbul. I had to apply for a grant from the Turkish Cultural Foundation to do it and I spent two weeks in Turkey finding musicians, photographing them, and interviewing them. It’s a project I'm so proud of and I went to find it and share the link with someone recently and most of it’s gone from their site—the gallery is missing and a lot of the copy is, too. I don’t know if it happened during an update or what, but it’s just so sad.

David: What's the value of slowing down for you creatively? How do you sell that idea to younger creatives that are used to the pace of social media and putting out a lot of work very quickly?

Ebru: I think it is a matter of quality versus quantity. That's one of the reasons that I get so irritated when I hear the word “content.” Social media made it so people see visual elements as something that you put out alongside other stuff to keep people's attention. I put too much into what I do to call it content. You only have so much control over what you do as a professional photographer and part of that control really comes from how you edit your photos and what you release. Slowing down and doing things the way I do lets me control the consistency of my work, and I think it is really important to put out only the things that I believe in 100%.

Neko Case by Ebru Yıldız

David: How do you approach capturing the energy of an artist or an album in a photo? For example, your shots of Boris and Uniform are heavily manipulated and shot in a really moody and artistic way, but those shots telegraph the sound of those bands beautifully. What did you go into that shoot hoping to capture?

Ebru: When I work on photos for album art, the artist already has a world built around the album before I make any of the visual elements. I usually spend a long time researching the artist, listening to their music, and trying to pull inspiration from the lyrics and the tone of the album. It’s about how the music makes me feel. Then I really plan and think of setups that would work with that, but nothing ever goes as planned. It can also be a matter of managing people and being flexible with where they’re at and being able to change direction. Sometimes you just have to let an idea go, which is hard for me to do. I like working on an idea until I exhaust all of my options.

You picked a really good one with Boris and Uniform because that's one of my favorite photos. When I think about Boris, I think of darkness, smoke, and aggressive, strong, piercing music. The same goes for Uniform, who have a really raw, dark, intense sound. With that shoot, I had those feelings in mind and that gave me inspiration for the lighting and the mood of the images. The challenge was I couldn't have the two bands in the studio at the same time and I had to figure out how to combine the two shoots so that they looked like they were shot together. Having to shoot the bands separately is how I came up with weaving the two photos together to merge them into one. I didn't want to just combine the two images in Photoshop because anybody can combine the two images to look like one. I really wanted something rawer.

So the direction those photos took came not only from the conditions, but from how I put them together to create a visual that would unify the two bands. I think those photos worked.

David: It sounds like the final images came really close to the vision you had in mind despite having to work around a bunch of logistical problems.

Ebru: I actually had had a surgery right before the Boris shoot and I was like “I'm not going to miss a chance to shoot Boris,” so I was actually in physical pain while I was shooting them. It was really brutal, but at the end of the day, it worked and I'm really happy with how those photos came out. And, because of that shoot, I got to do a zine with Boris. One thing always leads to another and I think artists appreciate it when they see you put so much into what you're doing.

Boris and Uniform by Ebru Yıldız

David: The psychology side of portraiture is massive. My favorite music images are made by photographers that seem to really gain an artist's trust. How do you go about getting inside an artist's head and gaining their trust–especially in a short period of time. For example, I know your photos of John Cale had to happen very quickly.

Ebru: I think it comes back to how much love you put into your work. One of my favorite things in the world is making photos and whenever I have my camera in my hand, that joy comes across immediately. I get really animated and excited. That energy is contagious and it makes the artist feel like they're doing something right, too. It becomes a good dynamic. The other important thing is people pick up on how much you care by how you direct them when you’re trying to make the photo better. Artists notice when you’re really paying attention and when you really want to make it look good. Having a good idea that resonates with the artist helps as well.

There's a Laurie Anderson shoot that I did and it was such a special shoot. She did a show where she talked about an interview that she saw with Yoko Ono on TV and when they asked Yoko how she feels about Trump, she started screaming and she wouldn’t stop. Laurie Anderson thought that was such a powerful thing, so she asked the audience to scream with her and everybody started screaming. It felt like such a profound moment. Whenever I talk about it, I get goosebumps. It really stuck with me and I thought if I got to shoot Laurie Anderson, I had to have the courage to ask her to scream. At that point, I didn't know if I was going to get to shoot her or not, but she came to the portrait booth and I told her how powerful I thought that moment was and I asked her if she could scream for the photo. She did a silent scream and I got through around four shots before she was like “Okay, I'm done.” It was so quick, but the photo is one of my favorite photos. I think she liked it, too, because her team has hired me to do her publicity photos a few times since. One of my biggest points of pride is that I got to work with her.

Laurie Anderson by Ebru Yıldız

David: That’s amazing. And it sounds like it was a positive experience and most of them have been. How do you go about managing personalities when it's a little more difficult, especially with groups?

Ebru: 99% of the time people do not want to be photographed, but it’s something that they have to do. I always say that I make my living from making other people miserable because most artists just want to get the shots and be done. I always tell artists how important it is to document themselves because you’re creating a visual history for your work and that it’s something they have to do, so they might as well enjoy it. I feel the responsibility of making something good for them because I know that it's going to be tangled in their visual history forever. Explaining that is really important when it comes to actually dealing with people that aren’t excited about a shoot.

“My aim is for you to feel how you really would in that person's presence when you look at a portrait I shot. I want you to get a feeling of their personality or I want to make you curious about the person.”

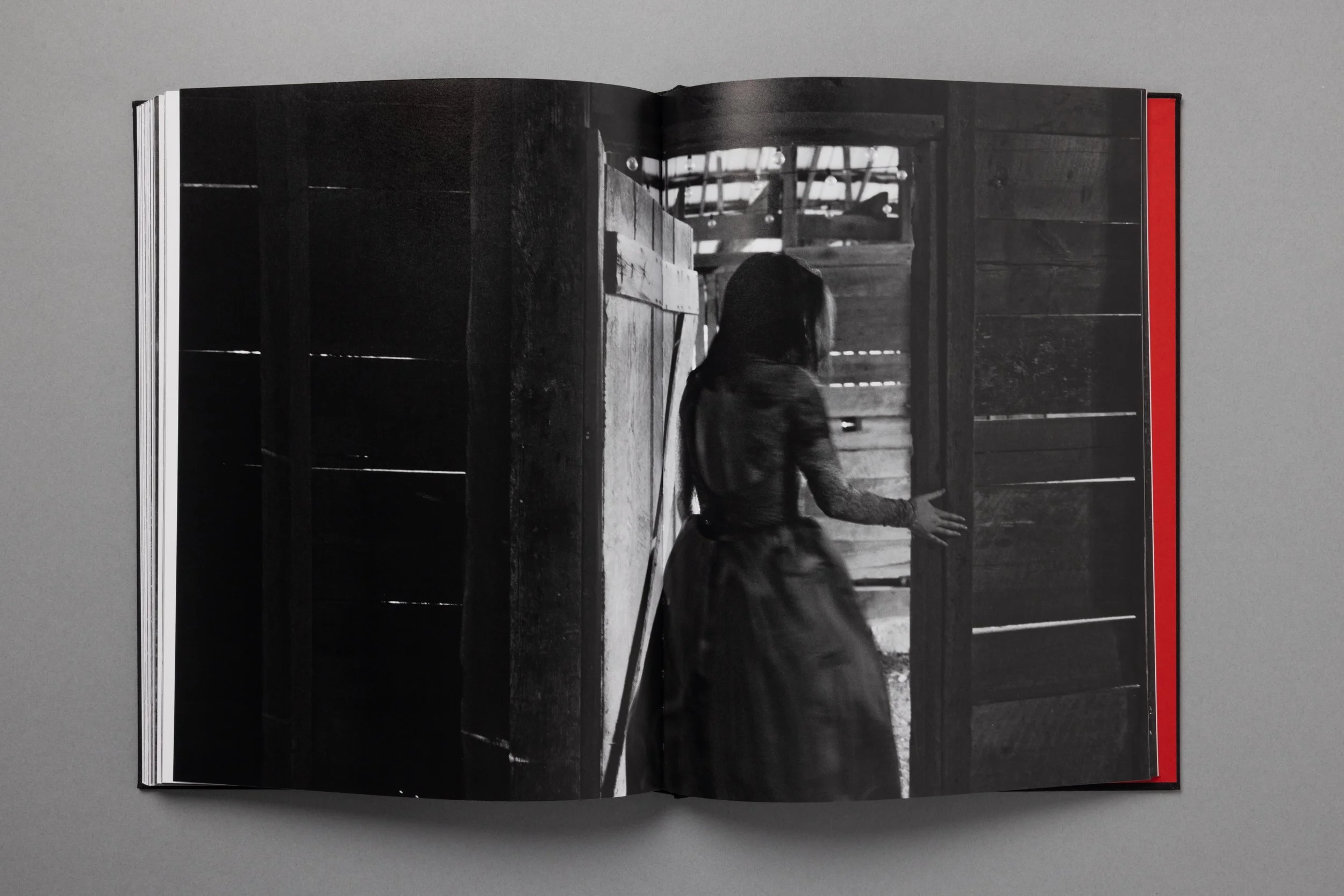

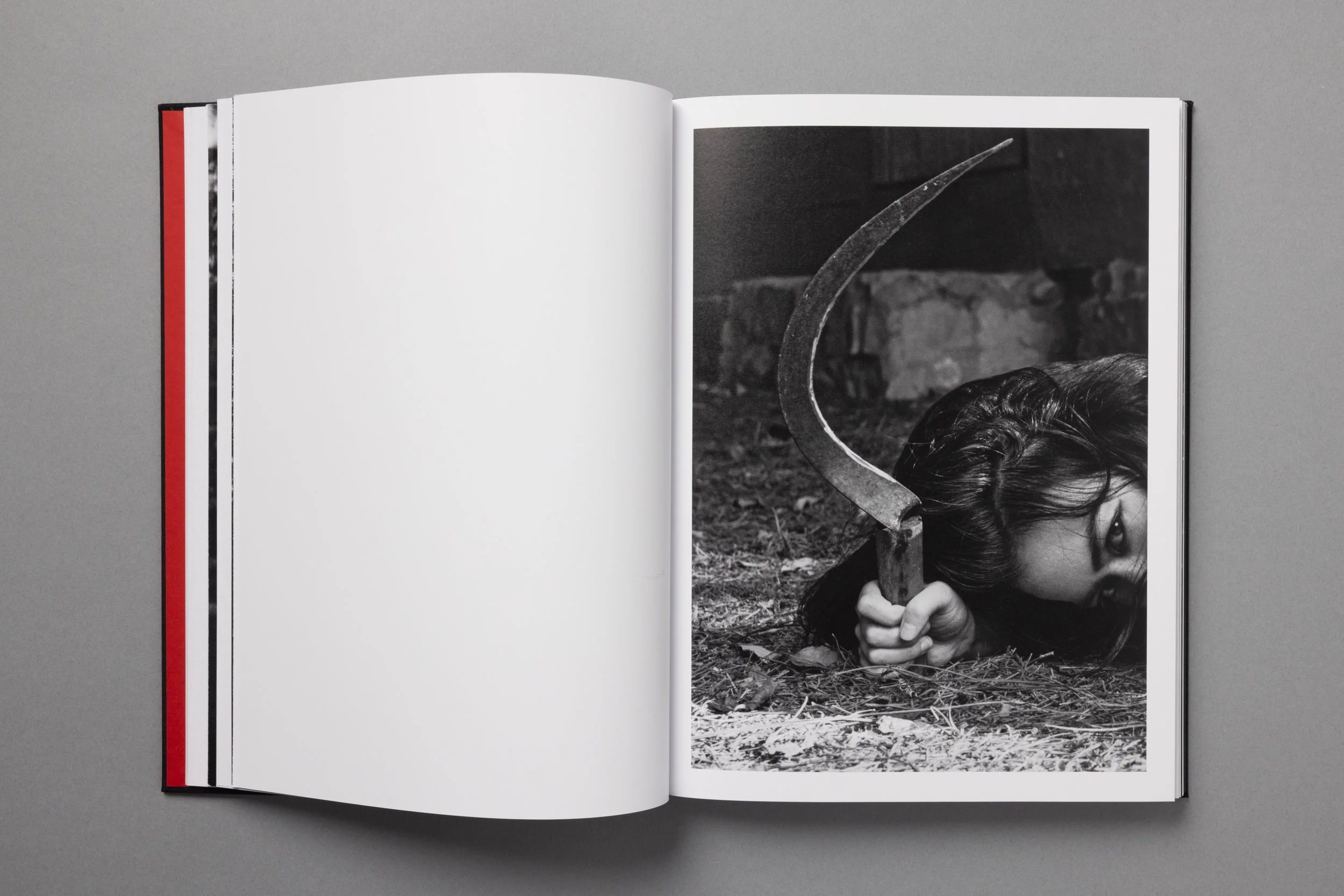

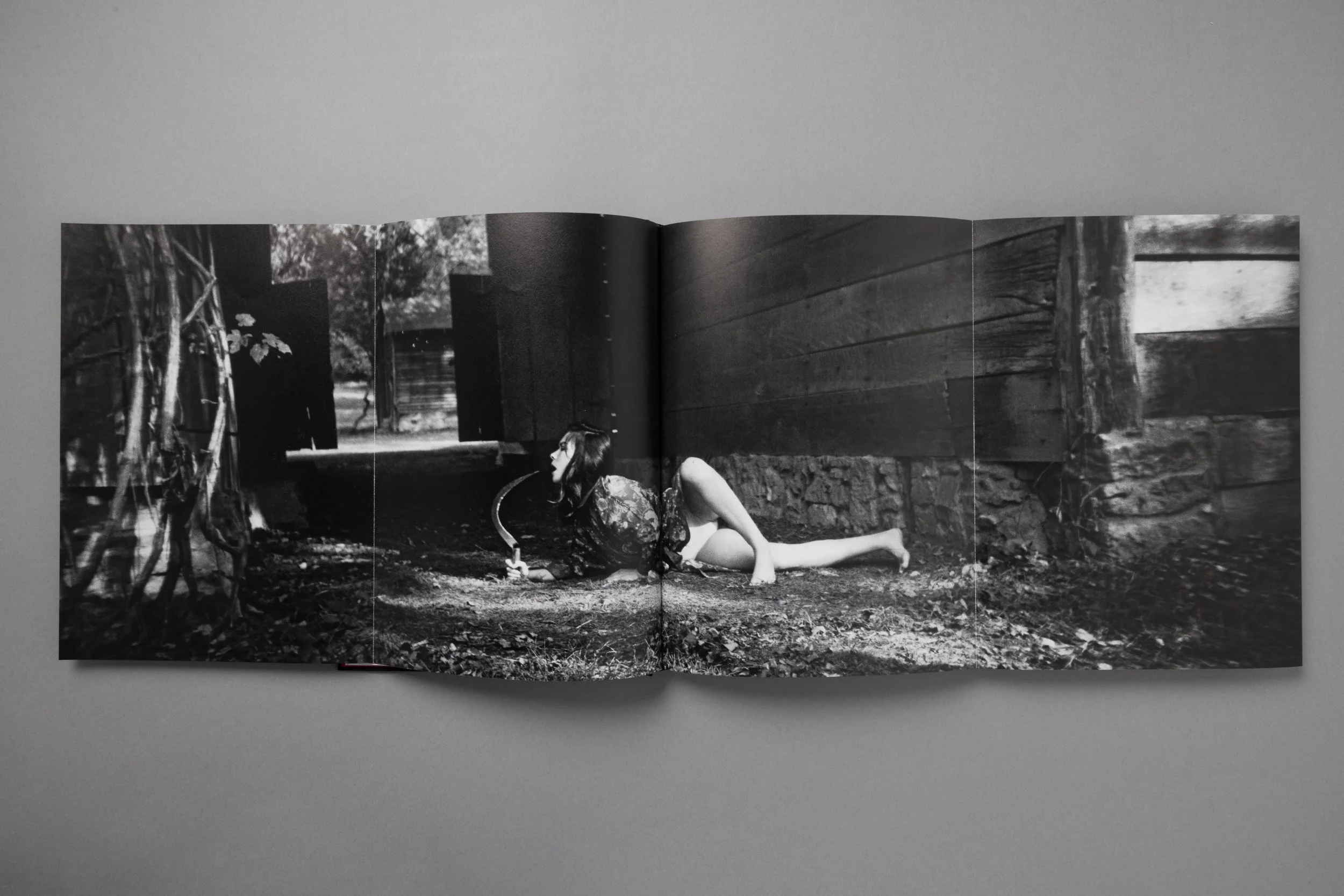

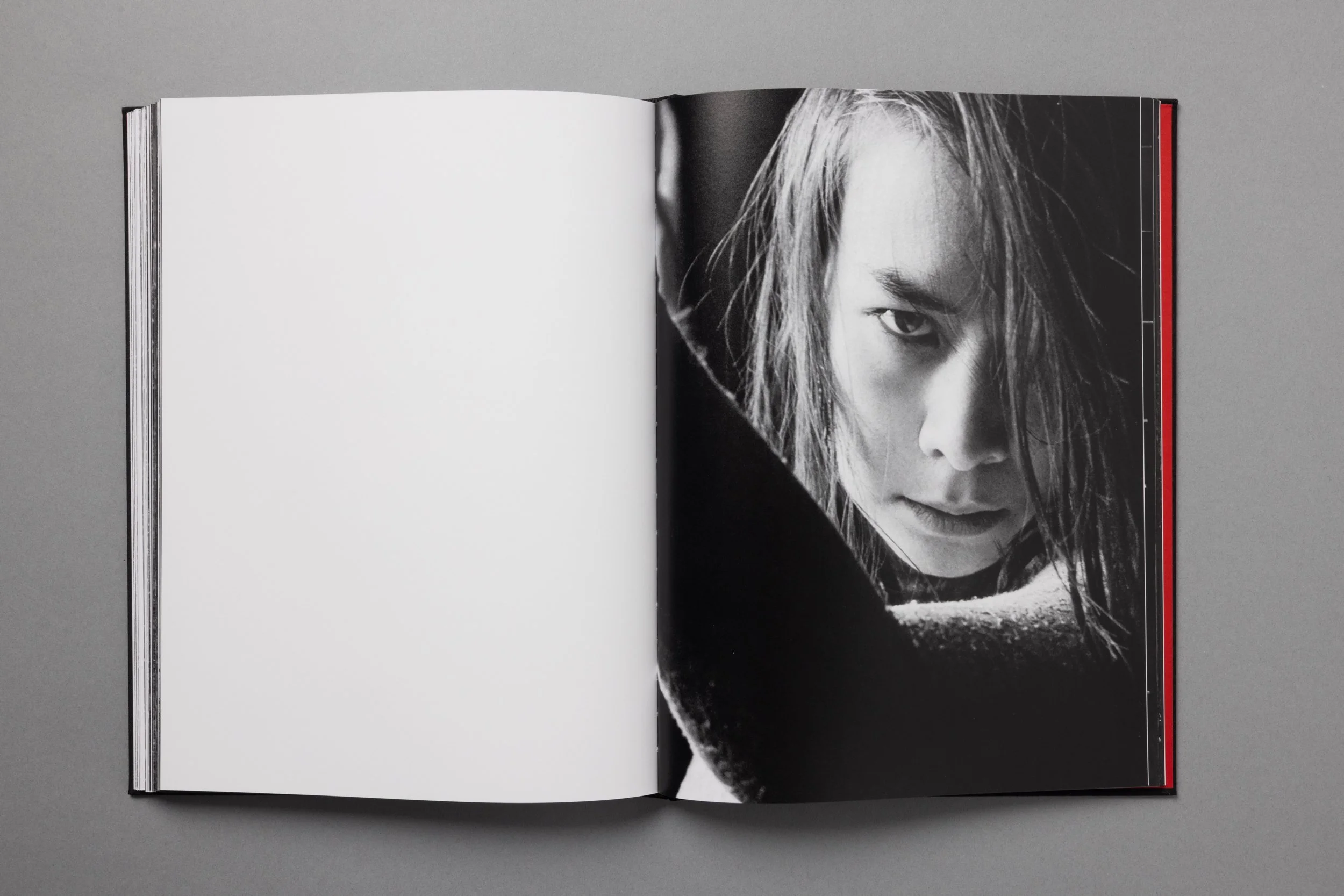

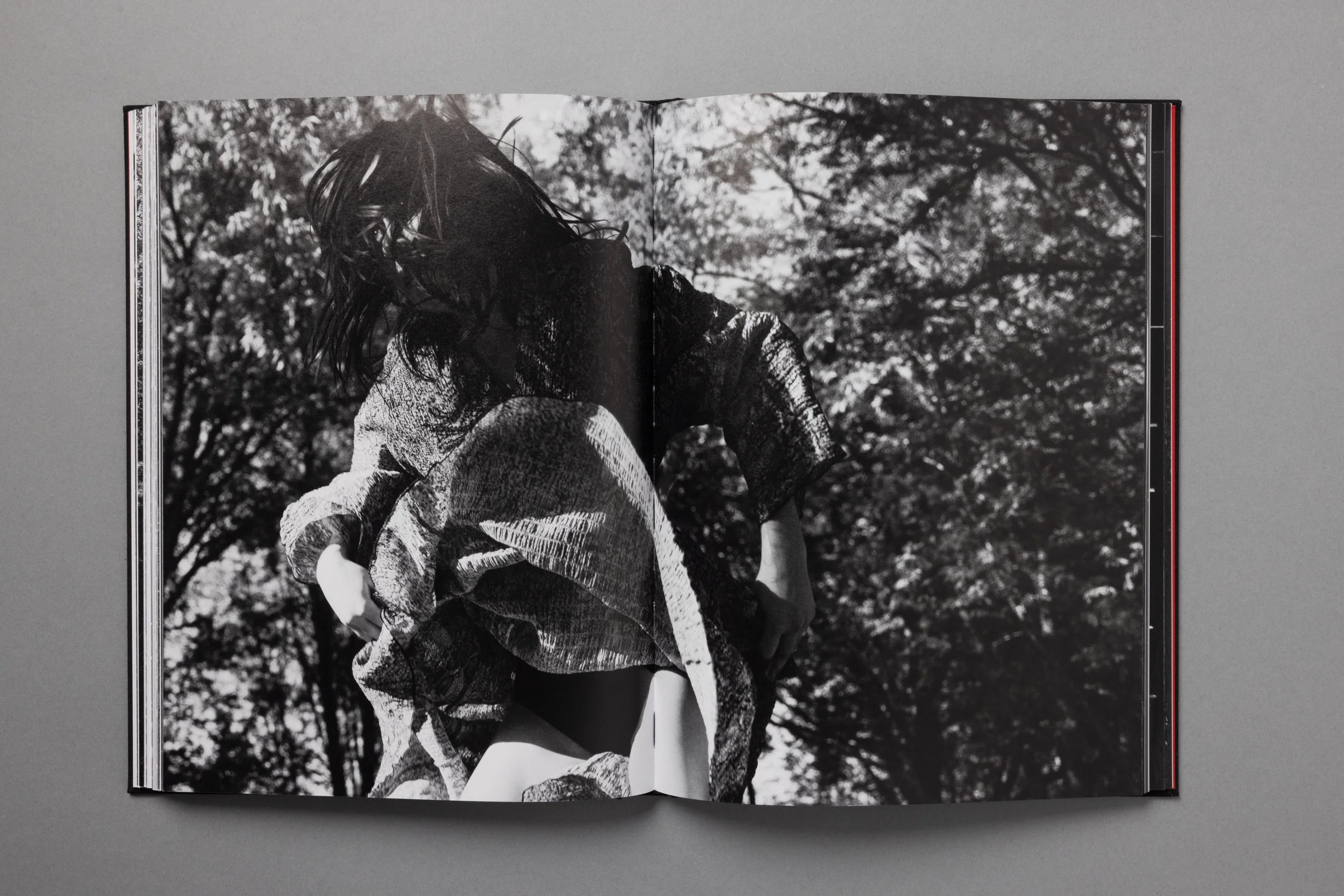

Mitski by Ebru Yıldız.

David: What defines a successful portrait for you?

Ebru: I just know it when I see it. My aim is for you to feel how you really would in that person's presence when you look at a portrait I shot. I want you to get a feeling of their personality or I want to make you curious about the person. I want it to bring up some kind of emotion in the viewer. On a different level, I think if my photo matches how the person I’m shooting sees themselves, that’s a success. Once you make someone feel comfortable, their personality is going to come across regardless of how they want to be seen. Everybody has a sense of how they want to be perceived, especially in the selfie era. But once they relax, they get rid of the mask and that’s what makes a really good photo.

David: I'm a huge David Bowie fan and I can’t think of a better example of a visual history shaping how we perceive an artist, but I also think his humanity came through in photos regardless of who the photographer was or what character Bowie was playing at the time.

Ebru: There's a reason for that! I was listening to a podcast with a photographer that he had a long relationship with and he said that Bowie was someone that even if you have five minutes with him, he’d be incredibly present and give you his best so that you can do your best. I think that's one of the reasons why there aren’t any bad photos of him. You can feel his presence in all those photos. And he really is the perfect example of what I'm talking about with visual histories. All the personalities that he went through, all the fashion choices he went through are documented and we are so lucky to have that visual history.

“Once you make someone feel comfortable, their personality is going to come across regardless of how they want to be seen.”

David: I don't think a lot of people think about photography, and especially portraiture, as collaboration.

Ebru: Yes, for sure. I recently announced a book that I made with Mitski and she's one of the best collaborators ever. It's incredible. I don't consider myself as a good collaborator because I don't really think about it, but Mitski makes me good at collaborating.

David: What makes her so good at it?

Ebru: Sometimes artists have an idea and then want to micromanage the shoot. With Mitski, she gives you really broad parameters and lets you go in whichever direction you want to. She trusts you with what you're doing and that's the best kind of freedom anyone can give you. When you feel trusted, you feel more comfortable experimenting and in some cases, being demanding to get a shot.

The shoot that we had for her last album was a three day shoot and we didn't even speak half of the time during it. She was doing her thing, I was doing my thing and it just made it so special. She wasn't concerned with how she looked and didn't want to see the photos as we shot them, which is rare because there's the expectation to see the photo during the shoot now that everyone’s shooting digital, which I think makes everybody feel so self-conscious that nothing good comes out of it. The first thing anyone sees when they see photos of themselves is what is wrong with it. It’s human nature, but the whole dynamic of a shoot changes because of it. So that was one of those magical shoots where she never questioned an idea, she just interpreted what I asked for and made it her own. To this day, I feel the same feeling that I had on that day when I look at those photos.

David: What's that feeling?

Ebru: Happy and content. Everybody talks about the flow state where everything seems to work and you are in the zone. Everything worked itself out on that shoot. With this Mitski project, everything has had a good energy around it. It's been a magical experience.

David: You still seem to find the time to shoot emerging artists despite getting called to shoot pop stars like Pink and legends like David Byrne and Laurie Anderson. I think the dream for many creatives is to find the balance between doing soul satisfying work and while getting gigs that can sustain a good life. Could you tell me a little bit about how you found that balance?

“If I’m taken by a band, regardless of where they are in their career, I get obsessed with making photos with them. I start thinking about how I can shoot them until I actually get to do the photos.”

Ebru: Obviously I have my own personal music taste, but at the same time, I am a working photographer–meaning I make my living doing this. There are so many factors other than budget that go into who I work with. My only criteria is really that the person can’t be an asshole. I try to do a lot of personal projects, too. If I’m taken by a band, regardless of where they are in their career, I get obsessed with making photos with them. I start thinking about how I can shoot them until I actually get to do the photos. So it’s really that I have to make those photos as a photographer. It’s really a matter of managing my time, which I'm not always very good at.

David: You have a really distinct visual style, to the point that I know that a picture is yours before seeing the credit. How do you go about finding your thing while still accomplishing what’s demanded of a photo?

Ebru: That’s actually a struggle for me sometimes. I think I’ve figured out how to put my own touch on things that are not necessarily my personal works lately. Obviously I love my shadows and I love using very little light and moody photos. There are things that are obviously my personality in my work. But then I get to work with a person like P!nk, and she’s larger than life and colorful and happy. There are some photos of her that I made that I love because they feel like an in-between moment, where they still capture her, but there's some of me in it as well. I recently did an album campaign for an artist named Molly Tuttle, who is an incredible guitar player. The whole album is really playful and it felt like the shoot needed to be colorful and bright. I managed to get my shadows in it, but the photos are still bright and playful. Those photos aren’t what people necessarily think of when they think of my work, but they’re still very me somehow.

David: What keeps you inspired? Is it ever a struggle to stay interested in music photography this far into it?

Ebru: Photo books have been a really big thing for me. I've been a collector of photo books for a long time. When you are looking at photos online, you spend a few seconds on them and move on. With a photo book, you really look at the images and you go back to them again and again. I find new photographers that are so all old school in how they do things through photo books. I try to keep myself inspired in that way.

Music is always at the top of my list for inspiration as well. Sometimes I hear people talk about music as if it's something you grow out of or something you're only passionate about when you’re young, but music plays a really important part in my life. There's always music playing somewhere in our apartment or in our studio. So that's definitely a big part.

When we were printing the Mitski book, I hadn’t seen some of the photos I shot for it that big prior to making the book. You see all these really cool details that way and even when I feel like I know every corner of the photos I’ve taken, having them printed in a book changes the whole thing. Photo books are like records for me. They're sequenced in a purposeful way and there's information in the back that gives you a little bit of the background on the photographer or the photos and it feels like sitting with an album’s liner notes. I love them for that reason.

Mitski by Ebru Yıldız

David: I find that across creative disciplines that involve gear in the way photography does, people tend to really fixate on the role equipment plays. Are you really into the gear side of photography or do you think it can become a distraction?

Ebru: You are asking the wrong and the correct person at the same time! I am not a very technical person at all and I find joy in the human element, the mistakes, and the things that show that a photo was made by a human. That applies to my cameras as well. I have a ton of cameras and I think I've used five different cameras for the Mitski book alone. But I think of cameras like guitar pedals–each one of them is good at doing something. You don’t have to have the most expensive camera to do that, and the centerpiece of the Mitski book is an eight page foldout of a photo that was made with a $100 plastic Holga camera. I have cameras that are expensive, so I'm big on owning cameras, but I don’t think you have to have anything specific to get the job done. It’s about whatever serves your purpose.